Right Against Torture and Degrading Punishment

The right against torture and other cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment or punishment is guaranteed under the 1987 Philippine Constitution, specifically in Article III, Section 12(2), which provides:

“No torture, force, violence, threat, intimidation, or any other means which vitiate the free will shall be used against him. Secret detention places, solitary, incommunicado, or other similar forms of detention are prohibited.”

This right is further reinforced by Republic Act No. 9745, or the Anti-Torture Act of 2009, which criminalizes all forms of torture and imposes penalties on those who violate the law.

R.A. 9745 Anti-Torture Act Summary

The Anti-Torture Act of 2009 (Republic Act No. 9745) aims to prevent and penalize acts of torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment committed by persons in authority, especially those involving law enforcement and security personnel. Below are the main provisions of the law:

1. Definition of Torture

Torture refers to any act that causes severe physical or mental pain and suffering intentionally inflicted for purposes such as obtaining information or a confession, punishment, intimidation, or coercion. This act is carried out by or with the consent of persons in authority.

2. Prohibited Acts of Torture

Torture includes a wide range of prohibited acts, categorized into:

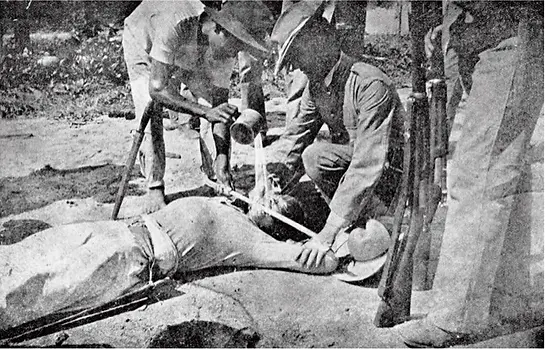

Physical Torture: Acts that cause physical pain and suffering (e.g., electric shocks, beating, cutting, suffocation, etc.).

Mental/Psychological Torture: Acts that cause mental or emotional suffering (e.g., prolonged interrogation, threats, humiliation, forced witnessing of torture, mock executions, etc.).

3. Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

The law also covers acts that do not amount to torture but still cause severe physical or psychological suffering. This includes cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment not intended to extract a confession but used to punish, intimidate, or coerce.

4. Rights of Victims of Torture

Victims of torture are guaranteed the following rights:

Right to Complain: Victims have the right to file complaints against perpetrators before any competent authority or body.

Right to Prompt and Impartial Investigation: The state must ensure that any complaints of torture are investigated promptly and impartially.

Right to a Medical Examination: A victim is entitled to a physical and psychological examination conducted by a doctor of their choice.

Right to Legal Counsel and Independent Monitoring: Torture victims have access to legal representation, and independent human rights groups are allowed to visit detention centers.

5. Command Responsibility

Superior officers or commanders who knew or should have known about acts of torture but failed to prevent, stop, or report them may be held equally liable as the direct perpetrators.

6. No Justification for Torture

The law emphasizes that no exceptional circumstances, such as war, threat of war, political instability, public emergency, or any order from a superior, can be used as a justification for torture.

7. Protection of Persons Involved in Torture Investigations

Individuals, including victims, their families, witnesses, and legal representatives, are protected from retaliation, intimidation, or coercion for their involvement in investigations.

8. Penalties

• The law imposes severe penalties on perpetrators of torture, including:

• Life imprisonment for acts of torture resulting in death or serious injury.

• Reclusion perpetua for persons found guilty of torture.

• Fines and civil liabilities may also be imposed.

9. Reparation for Victims

Victims of torture are entitled to reparation, including compensation, restitution, rehabilitation, satisfaction, and guarantees of non-repetition.

10. Non-Derogability of Anti-Torture Law

Torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment are non-derogable rights, meaning that these rights cannot be suspended or limited, even in times of emergency.

11. Obligation to Report Torture

Any public official, medical personnel, or government employee who has knowledge of torture must report it to the proper authorities.

12. Training and Education

The law mandates the training of law enforcement officers, medical personnel, and other persons involved in custody or interrogation on the prohibition of torture.

13. Monitoring Mechanisms

The Commission on Human Rights (CHR) is tasked with monitoring the compliance of detention facilities and law enforcement agencies with this Act.

These provisions collectively aim to eradicate torture in the Philippines and provide justice and protection for victims while ensuring accountability for perpetrators.

Violation of R.A. 9745

The legal implications of torture and extrajudicial confessions are significant, particularly in the context of human rights and due process under Philippine law and international legal standards. Both acts are considered grave violations of constitutional rights and are explicitly prohibited under several laws.

1. Torture and Its Legal Implications

Prohibition of Torture: Under Republic Act No. 9745 (Anti-Torture Act of 2009), torture is explicitly prohibited. Any confession, admission, or information extracted from a person through torture is inadmissible as evidence in court. The 1987 Philippine Constitution (Article III, Section 12) also provides that no person shall be subjected to torture, force, violence, threat, intimidation, or any other means which vitiate free will.

Criminal Liability: Anyone found guilty of committing torture is subject to criminal penalties, which can include life imprisonment or reclusion perpetua depending on the severity of the torture (e.g., if it results in death or serious injury). Public officials who fail to prevent or report torture may also be held criminally liable under the doctrine of command responsibility.

Civil and Administrative Liability: Aside from criminal prosecution, perpetrators may face civil liabilities in the form of compensation or damages to victims. Administrative penalties, such as dismissal from public office, can also be imposed on government officials involved in acts of torture.

International Responsibility: Torture violates international human rights obligations under the United Nations Convention against Torture (UNCAT), to which the Philippines is a signatory. Failure to prevent or punish torture may expose the country to international accountability mechanisms, such as investigations by the UN Committee against Torture.

Exclusionary Rule: In legal proceedings, any evidence obtained through torture is inadmissible. This is part of the exclusionary rule, which invalidates evidence obtained through illegal means (Article III, Section 12[3] of the Philippine Constitution). Courts must reject confessions or admissions obtained through torture, regardless of the truthfulness or relevance of the information.

G.R. No. 249274, August 30, 2023

Petitioners Aluzan and others filed a complaint against respondent Fortunado, a police officer, for violating Republic Act No. 9745 (Anti-Torture Act of 2009). The petitioners claimed that they were illegally arrested and subjected to physical and psychological torture while in police custody. They alleged that during their detention, they were beaten, electrocuted, and deprived of sleep to extract a confession. The torture allegedly resulted in physical injuries, severe mental suffering, and coerced admissions.

The respondent, on the other hand, denied the allegations and asserted that the petitioners’ confessions were voluntarily given during a lawful custodial investigation. Fortunado argued that the physical injuries sustained by the petitioners were not a result of torture but were self-inflicted or caused during their resistance to arrest.

Issue:

Whether or not Fortunado, as a police officer, violated Republic Act No. 9745 (Anti-Torture Act of 2009), and whether the confessions obtained from the petitioners are admissible in court.

Ruling:

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the petitioners, finding that Fortunado violated Republic Act No. 9745 (Anti-Torture Act of 2009). The Court determined that the petitioners were subjected to both physical and psychological torture during their detention, and that the confessions extracted from them were obtained through coercion, rendering them inadmissible as evidence.

Key Points of the Ruling:

1. Violation of Republic Act No. 9745 (Anti-Torture Act of 2009):

The Court held that the actions of respondent Fortunado, specifically the physical abuse and psychological manipulation inflicted on the petitioners, constituted torture as defined under RA 9745. The law prohibits acts that cause severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, that are intentionally inflicted by public officers for purposes such as obtaining a confession or information.

The petitioners’ accounts were supported by medical reports, photographs, and witness testimonies showing that they sustained injuries consistent with torture. The Court emphasized that the Anti-Torture Act of 2009 is designed to protect individuals in detention from inhumane treatment and to hold law enforcement officers accountable for engaging in such practices.

2. Inadmissibility of Confessions:

Citing Article III, Section 12(2) of the 1987 Philippine Constitution, the Court reiterated that any confession or admission obtained through torture, force, or intimidation is inadmissible in court. The Court rejected the respondent’s argument that the confessions were voluntarily given and pointed out that the petitioners were not informed of their rights nor provided with access to counsel during the interrogation.

The exclusionary rule under both RA 9745 and the Constitution mandates that evidence obtained through illegal means, including torture, cannot be used against the accused.

3. Criminal Liability of the Respondent:

The Court found Fortunado criminally liable under RA 9745, holding him responsible for engaging in acts of torture. The law imposes severe penalties, including life imprisonment, on public officers who commit torture.

The Court also highlighted the importance of command responsibility, stating that police supervisors who knew or should have known about the acts of torture but failed to prevent or report them could also be held liable.

4. Right to Reparation for Victims:

The petitioners were awarded compensation and other forms of reparation under RA 9745. The law provides that victims of torture are entitled to monetary compensation, rehabilitation, and restitution for the damages they suffered.

Legal Implications:

Torture is prohibited under RA 9745, and any confession or information obtained through such means is inadmissible in legal proceedings.

Public officers who engage in or tolerate torture face criminal, civil, and administrative liabilities.

Victims of torture have the right to seek compensation, rehabilitation, and protection under the law.

The decision underscores the importance of human rights protections during custodial investigations and the accountability of law enforcement officers for their actions.

Conclusion:

The Supreme Court acquitted the petitioners based on the inadmissibility of the confessions obtained through torture and found respondent Fortunado guilty of violating RA 9745. The ruling reaffirms the importance of upholding human rights standards and the strict prohibition against torture in the Philippines.

Extrajudicial Confession Obtained through Torture

Definition: An extrajudicial confession is a statement made by a suspect or accused person outside the presence of legal counsel and often before formal judicial proceedings. Under Philippine law, for such confessions to be admissible, they must be made voluntarily, with the assistance of counsel, and without coercion.

Exclusion of Coerced Confessions: Article III, Section 12(1) of the 1987 Philippine Constitution requires that any confession made during custodial investigation be voluntary, assisted by counsel, and conducted without physical or mental pressure. If an extrajudicial confession is obtained through torture, coercion, or intimidation, it is considered involuntary and inadmissible in court under the exclusionary rule.

Impact on Criminal Proceedings: In cases where a confession is the primary evidence, the exclusion of an extrajudicial confession obtained through torture or coercion can weaken the prosecution’s case. Without this confession, the accused may be acquitted if there is insufficient other evidence to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Right to Counsel: Under Republic Act No. 7438, a person under custodial investigation has the right to be informed of their right to remain silent and the right to counsel. Any extrajudicial confession obtained without the presence of counsel is inadmissible. The absence of counsel during an extrajudicial confession, particularly during a custodial investigation, renders the confession legally invalid.

Command Responsibility and Torture: Public officers, especially law enforcement agents, may be held accountable under the doctrine of command responsibility if they participate in, condone, or fail to prevent acts of torture leading to coerced extrajudicial confessions. This doctrine applies to superiors who knew or should have known about the torture and failed to act.

International Law: The Philippines is bound by international human rights treaties that prohibit the use of confessions obtained through torture. Under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), extrajudicial confessions obtained through coercion or torture are considered violations of due process rights and are inadmissible in legal proceedings.

Key Legal Implications:

Inadmissibility of Confessions: Torture-tainted confessions are inadmissible in both criminal and administrative cases under the exclusionary rule in the Constitution.

Criminal and Civil Liability: Persons responsible for torture and extrajudicial confessions, including law enforcement officials, may face criminal, civil, and administrative penalties.

Rights Violation: The extraction of confessions through torture violates fundamental human rights to dignity, due process, and protection from inhumane treatment.

Void Legal Proceedings: Legal proceedings that rely primarily on extrajudicial confessions obtained through torture may be nullified, leading to the acquittal or release of the accused.

Overall, both torture and extrajudicial confessions represent severe breaches of legal and constitutional rights. Courts place great importance on ensuring that justice is not compromised by the use of illegal and coercive methods.

Inadmissible extrajudicial confession obtained through torture

People of the Philippines v. Matignas y San Pascual, et al.

G.R. No. 126146, March 12, 2002

The accused, Matignas y San Pascual and his co-accused, were charged with robbery with homicide. The prosecution presented evidence including the extrajudicial confession of the accused, which was obtained during a custodial investigation. The confession was critical to the prosecution’s case.

However, the defense argued that the confession was obtained through torture and coercion, rendering it inadmissible. The accused claimed that they were subjected to physical maltreatment by the police during the investigation to extract the confession.

Issue:

Whether the extrajudicial confession of the accused, allegedly obtained through torture and coercion, is admissible as evidence.

Ruling:

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the accused, declaring the extrajudicial confession inadmissible. The Court emphasized the constitutional rights of an accused during custodial investigation, particularly the right to be informed of the right to remain silent and to have competent and independent counsel during custodial interrogation.

The Court held that:

The 1987 Philippine Constitution, particularly Article III, Section 12, protects an individual against the use of force, violence, or any other means which vitiates free will. Any confession obtained through such means is inadmissible.

The defense’s claim of torture and physical maltreatment was supported by the fact that the accused sustained injuries while in police custody, suggesting that the confession was not voluntarily given. The absence of a lawyer during the custodial investigation further vitiated the voluntariness of the confession.

Under Republic Act No. 7438, which provides for the rights of persons under custodial investigation, the presence of legal counsel is mandatory, and failure to provide counsel renders any confession void and inadmissible.

Given these violations, the Court declared that the extrajudicial confession was extracted under duress and through unlawful means. The accused were, therefore, entitled to acquittal due to the absence of admissible evidence proving their guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Key Points:

1. Torture and Confessions: The use of torture to extract confessions violates constitutional rights. Any confession obtained through coercion, force, or violence is inadmissible in court.

2. Right to Counsel: During custodial investigations, the right to be informed of one’s rights, including the right to remain silent and the right to legal counsel, must be strictly observed.

3. Inadmissibility of Torture-induced Confessions: Evidence obtained through torture, force, or other forms of coercion cannot be used in court, and any proceedings based on such evidence are null and void.

4. Command Responsibility: The case also highlights the responsibility of law enforcement to observe proper procedures and avoid the use of force during investigations.

Conclusion:

The Supreme Court acquitted the accused because the confession, which was crucial to the prosecution’s case, was extracted through torture and without the presence of counsel, violating the accused’s constitutional rights.